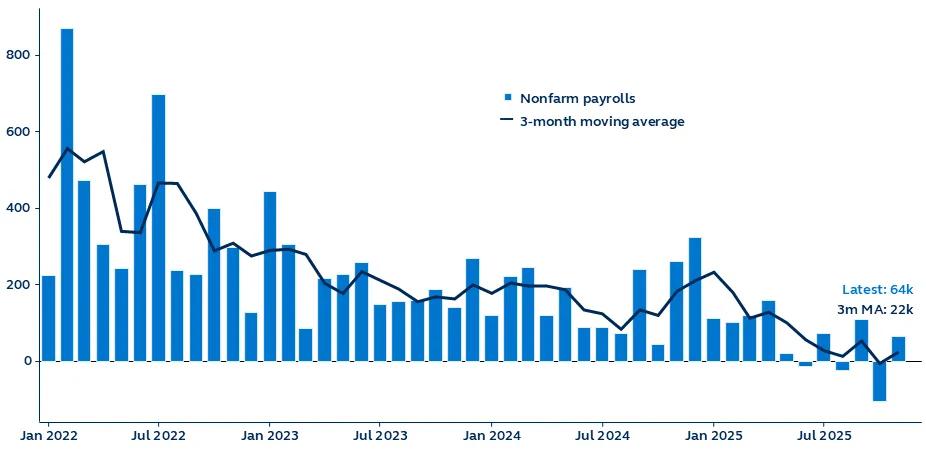

The U.S. added a modest 64,000 jobs in November, slightly above expectations, reinforcing the notion that the labor market is cooling but not collapsing. October’s report, delayed by the government shutdown, showed a contraction of 105,000 jobs—the largest monthly decline since 2020—almost entirely due to deferred resignations in federal government jobs that finally materialized in October.

For perspective, private payrolls rose by 52,000 in October and 69,000 in November, maintaining a modest upward trend since June, a stark contrast to federal job cuts experienced so far this year. While today’s data should be interpreted cautiously, given data distortions, the larger-than-expected rise in the unemployment rate will likely draw attention from policymakers, even as underlying conditions remain far from recessionary.

Notably, today’s release comes after weeks of data fog: the October unemployment data couldn’t be published, and the delayed publication of November's data had left policymakers with little visibility ahead of the December FOMC meeting. Nevertheless, data quality was unlikely to have been compromised, as the extended collection window for October and November payrolls resulted in higher-than-usual collection rates, improving data granularity. Moreover, the furlough of government employees during the shutdown did not impact employment numbers.

Thousands, January 2022–present

Source: Clearnomics, Bureau of Labor Statistics, Bloomberg, Principal Asset Management. Data as of December 16, 2025.

- Total non-farm payrolls increased by 64,000 in November, above expectations of 50,000. October’s report—largely impacted by the materialization of deferred resignations in federal government jobs—showed a contraction of 105,000 jobs, down from a September gain of 108,000 and meaningfully below consensus expectations for a 25,000 loss. The decline in monthly payroll numbers since the summer has fueled concerns about a weakening labor market. However, policymakers will likely interpret today’s data with caution, given the potential distortions.

- While October’s job losses look severe, the decline was almost entirely driven by a sharp drop in government employment, which declined 157,000 in the period and is down a total of 271,000 this year. This has been a result of DOGE cuts, with some federal employees who accepted a deferred resignation offer being removed from the federal payroll in October.

- Overall job growth in November was modestly positive, led by hiring in healthcare, social assistance, and construction, which posted its largest increase since September of last year. Professional and business services posted their first positive reading since April. Although these figures highlight the economy’s resilience, challenges remain—job gains remain concentrated across a few industries, while elevated interest rates and housing affordability challenges could still weigh on construction jobs ahead.

- On the other hand, several cyclical sectors continue to show weakness. Trade, transportation, and utilities shed jobs in November, led by sharp losses in couriers and messengers, a potential sign of cooling e-commerce demand. Leisure and hospitality jobs also declined. Lastly, manufacturing extended its decline streak, marking six consecutive months of contraction, likely reflecting a softening goods economy amid tariff-related pressures.

- Unemployment data for October was unavailable amid the lack of household survey data collection, given the government shutdown. In November, the unemployment rate rose by 0.2 percentage points to 4.6%, slightly above the expected 4.5%. This increase coincided with a higher labor force participation rate and a rise in labor market reentrants, the latter potentially due to federal employees looking for new employment despite a subdued hiring period. The decline in the duration of unemployment is another marginal positive, suggesting that while the labor market is softening, conditions are not in recessionary territory. Still, the rise in unemployment is likely to keep the Fed focused on its employment mandate.

Unemployment data for October is forever lost to history due to the government shutdown, while October’s payroll decline was almost entirely driven by deferred federal government resignations.

Meanwhile, November’s data should also be interpreted with caution; the labor market may not be as weak as the headline suggests, given data distortions and ongoing tighter immigration policies affecting labor supply. Still, the Fed is unlikely to overlook the larger-than-expected rise in the unemployment rate—now at its highest rate in four years—alongside the narrow breadth in payrolls gains.

While recessionary signals are absent, the cooling labor market should justify additional easing or at least a move toward a neutral policy stance. Given expectations that tariff-driven price increases will be a one-off and amid expectations for solid economic growth in 2026, the Fed may seek further evidence of cooling employment before its next cut. However, with the labor market clearly softening, more rate reductions are likely next year than the single cut currently penciled into the FOMC’s dot plot.

Investing involves risk, including possible loss of principal. Past performance is no guarantee of future results.

Views and opinions expressed are accurate as of the date of this communication and are subject to change without notice. This material may contain ‘forward-looking’ information that is not purely historical in nature and may include, among other things, projections and forecasts. There is no guarantee that any forecasts made will come to pass. Reliance upon information in this material is at the sole discretion of the reader.

The information in the article should not be construed as investment advice or a recommendation for the purchase or sale of any security. The general information it contains does not take account of any investor’s investment objectives, particular needs, or financial situation.

5069703